Isabella Lambert-Smith, University of Wollongong

Isabella Lambert-Smith, University of Wollongong

The high quality and thorough nature of scientific research into motor neurone disease (MND) helps us to better understand and find potential therapies for the disease. But how are MND researchers continuing their work with the challenges and restrictions of COVID-19?

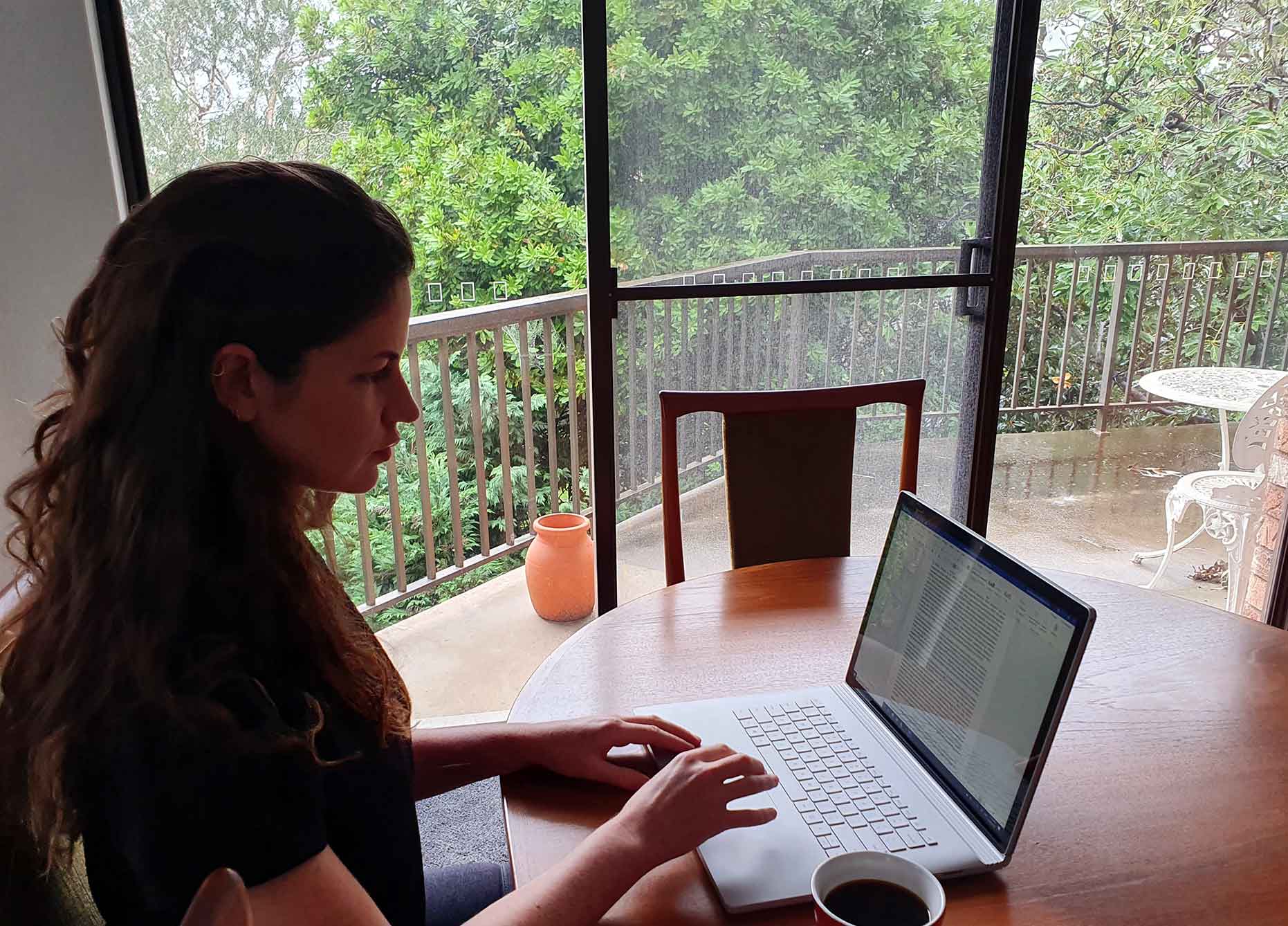

Isabella Lambert-Smith, from the University of Wollongong, shares her experience working in MND research during the pandemic, including what it means for lab experiments, the benefits of having more time to write up findings and why researchers are continuing to make a difference in helping create a world without MND.

By Isabella Lambert-Smith

The COVID-19 pandemic has turned mine and so many other MND researchers’ lives upside down. But I can assure you that those of us in research are working harder than ever to better understand and find potential therapies for MND.

With so much media focus on the virus and the urgency to find a vaccine, it’s natural to feel concerned that attention, funding and resources may be shifted away from MND. However, this is not the case; the focus on MND has not stopped. Research into MND is still moving forward. In fact, MND researchers are gaining momentum with their studies, despite the social-distancing measures and other challenges of COVID-19.

My research aims to increase our understanding of how and why motor neurones lose the ability to maintain protein homeostasis, and how it is linked with the genetic mutations that are detected in people with MND. As part of my research, I work with the brilliant and dedicated MND researchers at the University of Wollongong and have close connections with the MND researchers at Macquarie University.

I have continually been impressed by the camaraderie amongst everyone, and the strategies and innovations we’ve developed to adapt to the changing work environment at our universities as the COVID-19 pandemic has evolved. I can vouch for their persistence and ability to keep generating important research findings into MND.

Many of us are now working from home. This has provided us with a great opportunity to catch up on analysing data we’ve collected from our experiments in the lab. Sometimes, we can get so busy running experiments and collecting data about MND that we don’t get as much time as we’d like to analyse and make sense of what the evidence means.

For example, in much of my work I use cultured cells that carry the same genetic mutations that cause MND in different people to model and study the disease. I use these cells to explore how the genetic mutations affect different proteins in the cells and disrupt the way the cells function, and then how these disruptions can be alleviated by increasing or decreasing the activity of certain key proteins.

One way to test out how effective the key protein has been at improving the function of the cells is to examine the cells under the microscope and monitor if the cells continue to grow or if they die, and to see how the proteins inside them behave.

We collect quite an extensive amount of data from microscopy-based experiments like this and we use different software applications to analyse the data and make sense of it. Being able to work from home gives us the time we need to delve in and interpret what our new data means.

Another advantage of working from home is that we have more time to focus on writing up our findings into papers so they can be shared with other MND researchers. The dissemination of our findings through research papers is a crucial part of the research process.

We need to keep each other updated on our progress, particularly when we make any breakthroughs. This way we can continue to build on our knowledge and gain a progressively better understanding of MND. Writing papers and having them published also offers the opportunity to start the process of knowledge translation, which is how the evidence we collect in the lab eventually informs clinical practice.

Ultimately, everything we know about MND, its causes, and strategies to improve the lives of people affected by it, stems from the research we carry out in the lab and the clinic.

Knowledge translation is also how our findings make their way to being shared with the broader MND community, so that those affected by MND can remain up-to-date on what we know and understand about the causes of MND and how therapeutic strategies are developing.

The social-distancing measures pose new challenges to all of us in Australia and across the world, and like so many other people, my fellow researchers and I are communicating differently.

We use Zoom and similar video-conferencing technology to have regular team meetings and one-on-one discussions to talk through our research findings together. Emails are, as ever, another very important part of our communication strategy. We simply email each other much more frequently, as we aren’t able to pop into each other’s offices to discuss our work.

When it comes to progressing with our experimental, lab-based work, we have devised and continue to adapt lab management strategies. To comply with social-distancing and reduce how many people are in the vicinity at once, nominated researchers within our research teams continue to go into the lab to work on key experiments so that vital new data continues to be collected.

The lab can often be very busy with researchers working in close physical proximity to each other as we share bench space and equipment while gathering evidence from our experiments, so having fewer people in the lab allows us to keep a safe distance between each other to reduce the risk of spreading any infections.

The discoveries and advances that have been, and continue to be, made throughout this COVID-19 pandemic are promising and inspiring. As researchers have more time to focus on writing up and publishing their ideas and findings, we are forming a greater collective understanding of MND.

For instance, Professor Justin Yerbury of the University of Wollongong, together with his colleagues Natalie Farrawell (Senior Research Assistant) and Dr Luke McAlary, have written an insightful opinion piece on MND, 10 years’ in the making: Proteome Homeostasis Dysfunction: A Unifying Principle in ALS Pathogenesis.

The piece brings together key ideas about the causes of MND and provides much-needed clarity amongst its complexity. In particular, they identify and discuss how many of the known risk factors and causes of MND, such as genetic mutations, environmental toxins and activation of human endogenous retrovirus (HERV) genes (HERV genes make up approximately 8% of our genome) converge in their relation to a widespread imbalance in the billions of protein molecules that reside inside motor neurones. This work provides a valuable framework that will help MND researchers develop improved, targeted therapeutic strategies for people living with MND.

Many other MND researchers are making important contributions, too. Researchers are continuing to better understand the genetics of MND and how alterations in communication between motor neurones contribute to MND. Evidence is being collected about the potential role of gut microbiome alterations in MND (for a good summary on this area of research, see Dr Derik Steyn’s article in Spotlight on MND).

We know more now about how environmental factors can influence the development and progression of MND, as well as the ways in which metabolic changes are involved in MND. Potential therapeutic strategies continue to be developed and tested. There is so much more beyond what can be covered here too, demonstrating the need to keep supporting so many advances in MND research.

One of the major things I’ve learned during the COVID-19 pandemic is that this is a collective disruption. We are all coming together more as a community. And this includes the community of MND researchers, who continue to gain momentum in their research.

I believe that working more as a community shows not just our commitment to finding ways of helping those living with MND, but how much more is possible in trying to put an end to this disease, no matter what challenges face us.

So, please know that despite the upheaval COVID-19 has caused in all our lives, MND research is moving forward. As the pandemic forces me, other MND researchers and indeed all of us to adapt to new ways of living, it also helps create new ideas and insights. And we are coming together like never before to gain a clearer understanding of this terrible disease.

Isabella Lambert-Smith is currently completing the final revisions of her PhD thesis at University of Wollongong. When not working on MND research, Isabella enjoys spending time with her family, friends, and her dog, Monty, dabbling in drawing and painting, listening to music, reading, swimming at the beach, and keeping active (she is particularly fond of yoga and running).